Making Use of the Worldview Narrative

Does a book of poems need a narrative arc?

Many poets naturally tend towards autobiographical work, and their themes are deeply personal. To a greater and greater extent, poetry collections center around organizing events, principles and, yes, narrative structures. Doing so can make for powerful combinations of poems and can lead the reader through a more satisfying experience. Let’s look at the advantages of gathering these individual moments and pieces of poetry into a “story” that feels coherent and complete.

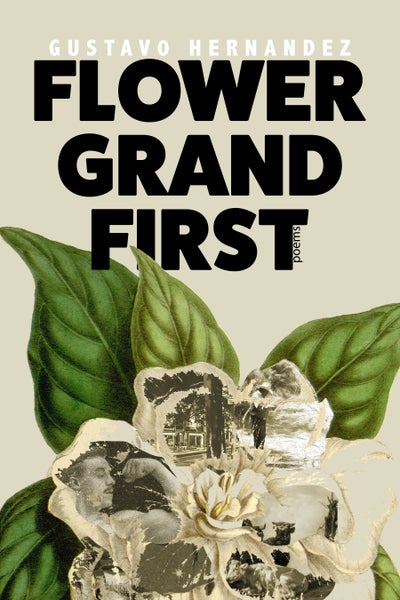

At The Poetry Salon, I’ve been discussing these narrative structures in our exclusive Build the Backbone of Your Book class where students are asked to combine archetypal narratives with poetry to create a satisfying “story” with their collections. So I was thrilled when Gustavo Hernandez, recent author of Flower Grand First (2021, MoonTide Press), brought up the “coming of age” story when discussing this debut collection. Talking about his writing practice, Gustavo told us, “The thing I love to read most is short fiction.” So as the pieces of his first book were coming together, he realized this was his coming of age story in poetic form. This kind of character arc offers a natural guide for many writers of poetry to follow.

What is a “Coming of Age Story Arc?”

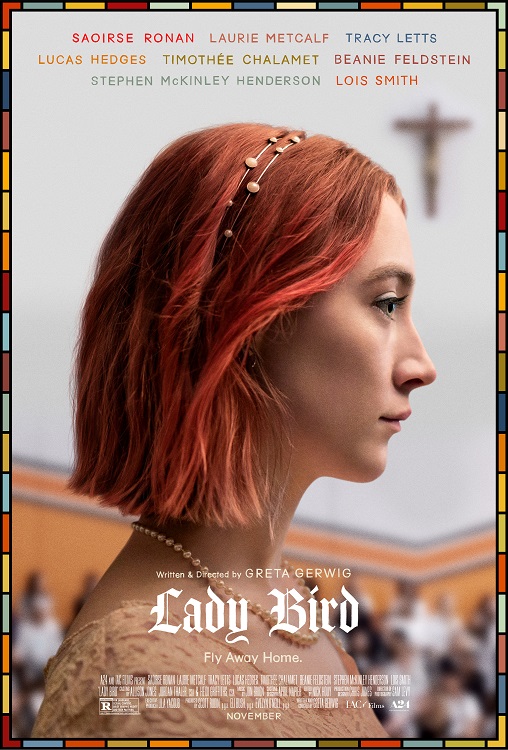

Whereas other story structures tend to focus on a character trying to achieve a specific goal or a hero gearing up for the resolution of a specific conflict, the “coming of age” story arc is often about a character navigating and discovering themselves as they try to master multiple areas of their lives. Think about Greta Gerwig’s 2017 film “Ladybird”, about a teenager, played by Saoirse Ronan, preparing to leave for college. Although the move to the next stage of her life might seem like the main goal of the movie, there are several sub-goals or mini-dramas she must face along the way – losing her virginity, going to prom, fighting and making up with her best friend, auditioning for the school play. In an interview with Ronan, Stephen Colbert said, “In most movies you’re waiting for the big explosion, but in this movie the big explosion is every single scene.”

Isn’t this true of a collection of poetry? Each moment is its own mini-drama wrapped up in a tight package, and collections like Flower Grand First seek to tie these explosions together to form a full arc. In many ways, the coming of age genre is a natural choice for a writer’s debut poetry collection. It is about the shifting sands – those rites of passage that frame and motivate a becoming, that transformation from caterpillar to butterfly. And any story about change and transformation has multiple steps. The task of the poet is to weave those poems – the moments – into a collection of poems, i.e. an arc.

A series of poems collected to form a narrative identifies multiple points along the speaker’s journey. It draws a reader through the full experience of the transformation across time and quite possibly across space. You could even argue that doing this across multiple poems, fragmenting life moments, ideas and perspectives, is closer to actual lived experience than a more unified prose autobiography.

What are the Main Features of a Coming of Age Story Arc?

Typically, a coming of age story shows a main character exploring several aspects of their life as a person with growing responsibilities and freedoms. These include relationships with new friends, first sexual encounters, growing independence from family, and often a realization that authority figures don’t have it all figured out either. The speaker then feels motivated to find their own way through.

Gustavo’s book is a wonderful example of a young man’s struggle to become an adult, with all that entails for him. Being the son of two immigrants from Jalisco, Mexico he must navigate not only the “typical” coming of age concerns, but also a divide between physical worlds. Hernandez says he was “physically raised by California”, while at the same time haunted by his parents’ relationship to Jalisco, Mexico. The speaker of Flower Grand First must honor what he has learned from his family and still find a way to strike out on his own, seeing how he is different from his family. In this collection, Hernandez walks us through many “coming of age” beats. There are moments when he bonds with his sister, Carmen, who watched telenovelas with him as a child. There are moments when he reflects on his mother’s uneasiness about dusk, facing the darkness in a new land that to him is familiar. There is a moment when he almost, but doesn’t quite realize that he is gay while listening to music…

Flip the tape over again.

And the sparrows and the neighbors and my parents

can’t quite seem to

ask me why. They’re

not ready. I’m not ready,

but the DJ knows what’s up.

Towards the end, the book also deals with one of the major blows that often punctuates a coming of age, which is the death of a parent – here, Hernandez’s father. The final poem “Hereafter” is a tribute not only to the speaker’s father but also to what his father has made, asserting, “The hereafter is, like everything else around me, built by my father.” This poem describes the landscape of Jalisco, and in a way that I find poignant, asserts that, “After all these years we finally set out for the right horizon.” This final piece navigates that tension between continuing to love one’s roots and being forced to reckon with their loss.

Each one of these moments is its own revelation, its own drama of discovery and change or even hesitation, but added together they tell that story of a larger drama of becoming an adult.

You can write a coming of age story at any age.

In this excellent article, How to Write the Worldview (Coming of Age/Maturation) Story, Rachelle Ramirez notes that a coming of age story can take place anytime a person enters a new phase of their life. Commonly these stories are told about teens becoming adults or children losing their innocence, but they can be about grown adults starting a new job, becoming a parent, becoming an empty-nester, retiring, or approaching death. Any such journey offers opportunities for mini-dramas, mini-discoveries as the speaker discovers new aspects of themselves and learns how to find their way into and through the new stage of life. In other words, whatever story you are trying to tell, you can use the traditional arc of a “coming of age story” or a “worldview story” to organize the arc of the character’s journey.

If you want a beautiful example of how individual poems can tell a worldview story, check out our interview with Gustavo Hernandez, and buy his book, here.

Exercise: Think of a time you entered a new phase of life. What events shaped your view of that new phase, that new “world?” Make a list of moments. Consider who were your allies, enemies, mentors? How did you conform? How did you assert your individuality? If you can answer each of these questions, you can write your own worldview arc.