I was in a poetry workshop where a talented poet wrote, “I had to burn my brother’s body in order to stay alive during the night.”

I responded, “Oh, how sweet; the brother sacrifices himself in order to keep the sister alive.”

My neighbor said, “No, that’s not it. She’s empowered. She killed her brother in order to take care of herself.”

The instructor said, “You can shorten this to ‘I burned my brother and lived off the warmth.’”

The writer said, “I have no brother. Everything in this poem is a lie.”

Once it is On Paper, a Poem Belongs to Whomever Reads It

Writers often think their language belongs to them, that their poems in some way are their children. They get very personal about them, even downright precious sometimes. They become demanding. Stultifying. Very un-zen.

But language, once it is on the page, belongs to everyone.

It’s always doing its own kind of thing. Like children, you might think your poem belongs to you because you made it, but as every parent will tell you, children have minds of their own. Ask any two people what they think of when they hear the word ‘heart’, and you will find the many different associations a single word can provoke.

Poems, composed of words none of us made, can never really belong to us. Can never really reflect us as people. The word poetry, in fact, means “a made object.” It’s an invention, like a jungle gym or a theater or a snow globe, and not a stand-in for the person who made it.

Poems Have Multiple Meanings

Any kind of personal writing is part of the universal human desire to be seen. They want their poem to mean something, usually something specific – the one thing that they wanted you to know about their inner life or lived experience. It’s like saying to the fish that you want it to understand ‘hook’ as a representation of your earliest childhood memories or ‘boat’ as the longing its creator had for the sea. That is not what a hook is. That’s not, for all practical purposes, what a boat is for.

It’s like saying you want a flock of parrots to be just one color. Or you want a penguin to serve you caviar. Or you want a platypus to make up its mind about whether it is a mammal or if it can lay eggs. A poem isn’t a symphony of a single note that only one musician knows how to interpret or play.

Japanese gardens; chardonnay; Beethoven’s Second Piano Sonata – these are not things to be narrowed into one meaning that their creator intended. They are meant to be enjoyed and evoke feelings in a receptive audience. The real question to ask during any poetry workshop is, does each line evoke a feeling? And this one? And this one? Never you mind which feeling. That is something on which we are free to disagree about wildly, so long as the piece provokes something inside of us.

A poem is, as Joy Harjo says, “A house for the spirit.” It’s meant for the reader to feel the presence of something that may or may not have visited the writer herself. When I ask myself, ‘for whom do I write?’ I can never settle on a single answer.

Maybe it’s true that we write mostly for ourselves during the finite act of creation. We write because we enjoy the process of being in charge of our own little world, of imbuing a page with our thoughts and memories, of casting our spirit into the wet clay and gratefully leaving behind the demons that haunt us.

Fair enough, but that begs the question, for whom do I re-write? For whom do I edit? For whom do I publish the work when it is done?

It’s a paradox. Poems belong as much to the ones who read them as they do to the ones who wrote them. More so, maybe, because the ones who write them will move on and eventually pass away, while the creation itself lives on beyond the solace it provided to their creators. Poems, in that sense, is more for the reader than it is for the writer in the same way the Tao was for the Taoist more than for Lao Tsu. The poem is coming through you to them.

In a way it’s a little like prayer. You wrestle with angels in order to best them, for your own benefit, but if you do it really well, you get to bring those bested angels to others and say, “Hey, here’s an angel I caught. Ask it to grant you a wish.”

We Find What We’re Already Seeking

When Joy Harjo calls poems a house for the spirit, you can ask, whose spirit? The writer’s? The readers’? Some invisible force that transcends them both? What kind of spirit? There’s a reason I don’t like every poem I read. Bad poems are those that aren’t complete and don’t contain a spirit. Others just contain spirits I can’t recognize. Spirits I don’t want or have never been a part of my house.

You can see poetry as a reflective surface. The poems we read pull out thoughts that were already in us. People think that when they comment on a poem, they are saying something about the writer, but really they are telling us everything about themselves.

I once heard that you should read Gatsby at three stages in your life. When you are young it is about unrequited love. When you are in your thirties it is about the American Dream. When you are retired it is full of regret.

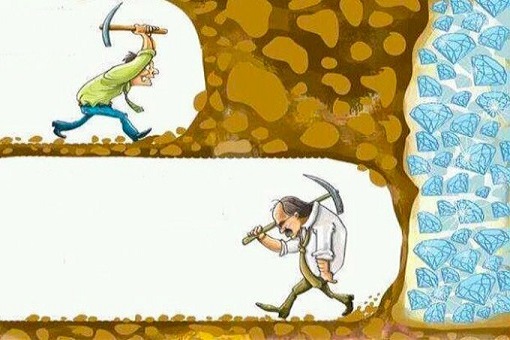

The richest poems are multi-faced diamonds. They reflect different things depending on where you stand or who you are. It has taken me years to realize that this is a feature, and not a bug. It is up to philosophers and politicians to verify small truths and narrow the world down into its measurable and historical accuracies. Things on which we can agree. It is up to the poet to create a meaningful chaos that helps us feel and experience, rather than merely understand.

An Outstanding Rule of Thumb When in a Workshop

If nine of ten poets can all agree on what a poem means, and there is no debate or controversy, you’ve made it too clear, which usually means too simple. Re-write it using a few more turns and monkey wrenches. What have you not said? Where have you not been fully honest? Can you locate your own doubts about the piece? About your life?

If nine of ten poets say, “I’m not sure what you are trying to evoke here,” it is too vague or complex, or you may have stumbled in and out of the poem’s core too many times to create cohesion. Clarify. Simplify. Rewrite with language that’s more accessible and easier to understand.

If nine of ten poets, or even six of ten tell you, “This is evoking something for me,” while each one offers different interpretations, the poem is working. Ignore the four poets who don’t get it or like it. Leave the six poets who do like it to happily argue about the poem’s meaning. You leave class early and send your finished work to The Paris Review.