Something that is essential can’t be taught; it can only be given, or earned, or formulated in a manner too mysterious . . . still, (poets) require a lively acquaintance with the history of their particular field and with past as well as current theories and techniques. Whatever can’t be…

blog

There is a flotilla of actual research that suggests kids already think like poets. They notice imagery, think in metaphors, and act as though everything is alive and has human consciousness, from their real pet frog to their stuffed giraffe. All I had to do was introduce a concept like “personification” or “metaphor” and let them dash away with their pens and paper into the happy land of kid speak. They would come back with Pulitzer Prize winning lines like, “Earth, do you enjoy spinning?” or, “I heard a caterpillar’s heart breaking when it turned into a butterfly.” When writing poems about science, one little girl wrote, “Pluto is not a planet. It is a tear the first astronaut cried when he saw our world spinning alone in space.”

The thing about changing your writing, unlike changing your life, is that it is much easier. You don’t have to max out your credit cards on a trip to Italy, find a guru in India, or go to Bali to fall head over heels. (#EatPrayLove.) All you have to do is change your words. Words are the building blocks of poems, and hence, the building blocks of your ideas; your style; your substance. If you change the words, and the way you use them, you change everything – and that means both inside and out.

To hear this blog read aloud by Tresha Haefner, click the triangle below or go to this YouTube Video Nothing tells you how much you need to write like being confronted by a new place. When my husband and I went on our honeymoon to Alaska, I made the mistake…

Hi All, I’ve so enjoyed writing these weekly blogs about creativity, and hearing everyone’s heart-felt responses. Now I want to know more about what you think? Do you have questions about how creativity works? Do you have challenges in your own creative life that you would like some help with?…

Americans have a funny relationship to money. We think that money will buy happiness, and unhappiness will bring us money.

From a young age, I knew I wanted to spend my life making art (poetry hadn’t yet entered my existence), but I also really, really wanted to have money. I worried that if I did something that made me happy, like futzing with poetry and making a mess with finger paints, I would have no money. So, I compromised and became an English teacher, which sometimes made me happy, sometimes made me very depressed, often made me tired, and absolutely did not make me rich.

There is a myth about writing – all art in fact – that it takes a special personality to do it. A special visionary with a special set of skills, handed down by God at birth, to distinguish the true artist from all other beasts of burden working in the field. The artist has a special sensitivity, a gift for seeing, an affinity for language that puts him or her in a category above other people, the way saints are elevated in the Catholic Church after curing the blind or allowing kings to pull their body apart on a rack.

I never have writer’s block, and my husband hates me for it.

If you ask him, or any of my friends or family really, they will affirm that expressing what I’m thinking is not my issue. There are no end of things to discuss and no end to my valuable opinions about them, and since most of my friends know this and avoid taking my calls as a result, I have nobody to tell about my opinions except the page. The page never talks back. It’s a great listener. When I write a first draft, I don’t care if it is good because I can always delete it before some analog human comes along with opinions that are different than mine (i.e. wrong).

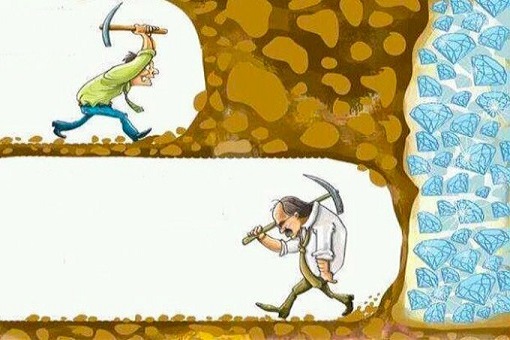

I think a lot of folks suffer under the illusion that you have to be born with a special talent, or else you’re sunk. The truth is, like most things, writing can in fact be learned. Like heart-surgery, or using Excel, or making a good quiche Lorraine, writing is a skill. The question is not, “Am I good at this?” but, “Do I like doing it?” Do I like writing, or reading other good writers, or sitting at a desk, staring out a window, contemplating the sound of the rain? If so, then keep doing it, even if you’re not good.

Click on the triangle below to hear Allen Rubinstein read this blog entry! For those who suffer from “fear of success” I have a modest proposal: become a professional artist. In all those non-artist careers I’ve never had, people apparently learn how to be a spit-shined, double-breast-suited success, turning out…